At Least Three Forms of Light Pollution

In which I try not to sound too distressed about living in the city and end up thinking about William Blake, again

‘Moonlight’ by JMW Turner (simply because I like the moon in this painting).

The moon is a rust-coloured coin. It has risen just above the roof of next-doors shed, a sliver of dark blue sky between it and the corrugated metal. The surface of the almost-full moon is different today: the craters look like the smudge of a thumb print. Wild-fires in America are responsible for the uncanny colour, apparently. If I squint, I can see that it is beautiful - a shape you might write poems about. The edges of the moon are still impossibly crisp, even in the haze. If this moon were perched above the peaks of mountains or a glassy sea, you could sit for hours in awe.

It’s not the shed that’s the problem, or even the roof-tops. I know cities can be beautiful. I’ve seen the same moon rise over the railway bridge on the river - pink (as we sit on a dusky pink sofa and watch a bat or two pass by). It’s been a golden coin in the water - and the ghostly galleon in the stormy city sky. I’ve seen it rise over the oil refinery while swimming in the Solent.

The problem is the light. There’s a security light right in my field of vision - stealing the brightness of the moon. It is so sensitive that it flicks on at the slightest wind in the bushes. It lights up the entire side of a house - and the light reaches a hundred feet or so to light up the top of my hedge - the side of my neighbour’s house - casting a bright twin in the conservatory glass. I cannot shut it out of my vision. I cannot appreciate the moon, even though I want to stand out and watch it rise. I loiter there for a little while, trying to decide if it is worth it. Whether I can put my hands up in a certain way to block out the security light.

There are moths in the garden, and they don’t seem to know what to do either. They flicker up from the grass and bluster towards the hedge, the light, the kitchen window.

(I’d like to run a moth-trap here, to see who is visiting the garden. But I think that security light would be brighter.)

When I was teenager, I used to think that poetry was about seeing the beauty in everything - and that being a writer meant having a privileged perspective on the world - one that looked at it with a sense of awe.

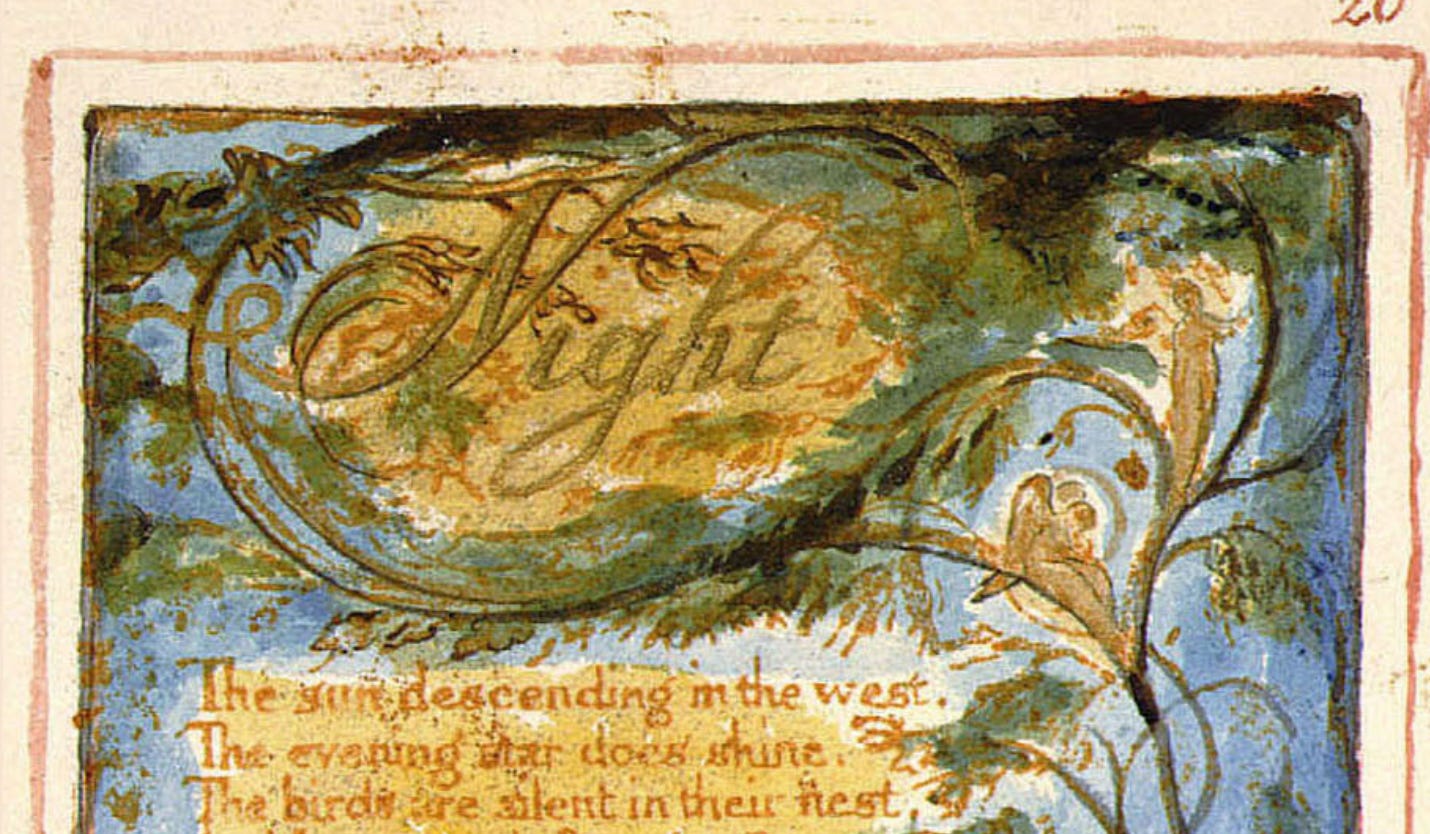

William Blake has always helped in this situation. When I first read Blake, I didn’t like it one bit. I thought it was too naive - to plainly joyful about the world (like the Introduction to Songs of Innocence - Piping down the valleys wild, piping songs of pleasant glee, on a cloud I saw a child…) It was only when a helpful English teacher (thanks, Ruth, if you’re reading this) explained that Blake was deliberately exploring how humans see the world, that I started to get it.

Blake knew that restricting our vision and our experience of the world to any one perspective was the limiting factor. This is embodied most famously in his depiction of London - where the streets and river are limited to their man-made paths - and the rules of Society: ‘the mind-forgèd manacles’ that not only constrain our creativity, but cause immeasurable suffering among the population who must live under unchallenged religious doctrine.

But Blake also knew that if we simply decided to exist in the opposite sphere - the pastoral idyll - the world of Innocence - then we were just as limited, just as constrained. If we only experience joy, we are doing ourselves a disservice.

It’s funny, because at that time in my life I was very much entrenched in toxic positivity - there is no problem that can’t be faced when you’re eighteen and the world is your oyster - especially if you suppress your own need for rest, push past any negative feelings about the world - and mask like your life depends on it.

There are many reasons why I fell into this, but today I’m really interested in how autistic joy (particularly over things that might seem unremarkable to other people - the colour of a fruit, the texture of a pencil - the shape of a rock) might combine with

alexythemia (a difficulty understanding your inner emotions in the moment) might lead to an unrealistically positive surface-level experience of the world (while subsuming or ignoring stressful or negative experiences). If anyone has found any further reading on this (I haven’t found anything on the neurology of autistic joy yet, for example) I’d be really interested.

But to return to Blake - who certainly experienced the world differently from his contemporaries (there’s lots of writing on Blake’s visions and mania - that I won’t go into here) - one of the his key realisations was that we simply cannot let ourselves exist in one sphere or another - we must live dynamically across Innocence and Experience, Good and Evil, Joy and Sadness - and that it is dialogue between these different states that unleashes our true creativity and true humanity.

One of my favourite examples of this is in Blake’s thoughts about his painting ‘A Vision of the Last Judgement’ from 1808. The painting itself is lost, but his original designs are still in existence - as well as his thoughts on the creative process in a letter to Ozias Humphrey.

I could spend some time talking about how Blake’s paintings embody his view of the world (to summarise slightly reductively, he wants the very act of painting to cross the binaries I mentioned above - and he hopes the viewer will experience this dynamism too). But I won’t go into that, because there’s a very small bit of his writing here that I’d like to pick up on - a vision that occurred to Blake while he was thinking about this painting - of two speakers talking about how they see the sun:

‘When the sun rises, do you not see a round disk of fire somewhat like a guinea?’

‘O no, no, I see an innumerable company of the heavenly host crying ‘Holy, Holy, Holy is the Lord God Almighty’’

One speaker sees the sun as a guinea; the other as a host of angels. Separately, each vision has value to the speaker - and certainly reflects their world views. Surely the speaker who sees the sun as a guinea must be avaricious or determinedly scientific; the speaker who sees it as a host of angels must be holy and enlightened?

But what Blake is really trying to tell us is that it is the dialogue itself - the push and pull between the two visions - that is the true enlightenment. It is the dynamic act of seeing, perceiving, thinking and questioning that enables us to experience the truth and poetry of the world.

This should probably bring me some solace, in my perception of the beautifully rusty moon and my anger towards the security light. If I try too hard to see the moon as beautiful, or get too stuck on the awfulness of the light - then I’ll become stuck (as I was, briefly, with my feet in the damp grass). The dialogue between these two things is what brings energy and creativity and prevents us getting stuck in either sphere.

In fact, it was that exact dialogue that gave me the energy to write this blog in one swoop. Interrogating the world and how I perceived it resulted in a burst of creativity.

And yet, I’m not fully sure if this was a useful exercise. I suppose the point of a blog is to share my creative process, my reflections on writing and nature - and a few accessible introductions to some of the academia that’s sitting somewhere in the back of my mind. So, getting grumpy at the security light wasn’t totally wasted.

I think the important thing here - as always - is not to let one train of thought (or one blog) get in the way of actually being creative. I’m not going to spend the next week thinking about Blake every time I sit down to write. In fact, getting stuck on theoretical approaches is exactly the opposite of what Blake would want. For Blake, dialogue isn’t academia. It doesn’t mean feeling less and analysing more. Dialogue should fuel creativity - whether that’s a state of mind, or actually making something.

So, I suppose it’s okay to hate the security light and love the shape of the moon, as long as I don’t get stuck in the garden, wondering grumpily if I can complain to someone about the light.

* I was supposed to be talking about the other issues I have with light pollution - but Blake got me sidetracked. Perhaps the lesson here is that I could turn them into poetry instead. The kitchen light that the neighbours leave on ALL NIGHT that shines into all of my windows. The time that I drove out to see the aurora and caught a few of the silky threads hanging in the sky - but never fully out of reach of the car headlights - or the return to the city from the forest.