‘The insides of writers’ heads resemble squirrels’ nests more than they do neatly arranged filing-cabinets’

Margaret Atwood

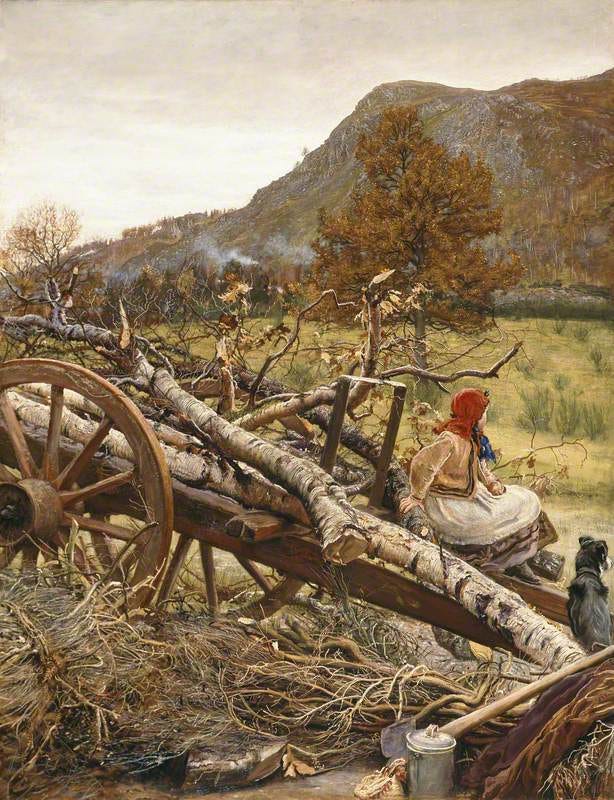

William Pratt, Gathering Firewood

After a little more than a year of debilitating burnout, my GP sent me away to be assessed for ADHD and Autism. As it’s a long process, I’m still waiting on some of the assessments - but what I’ve learned about my neurodivergence so far has been revelatory in terms of how I approach writing and how I see myself as a craftsperson - and also how I give myself grace, as a human being.

(I’ve also come to understand a lot more about my daily struggles - the ones that have been hidden from most people since childhood - and have impacted my work and personal life - but I’m not going to write much about those here as there are people who do that excellently, and I also don’t think the onus should be on the individual to explain their difficulties or the nuances of their diagnoses- plus, I’m easily distracted from the main purpose of my writing. But I’m very happy talking about these things in real life.).

Neurodivergent burnout is different from depression, and it’s different from work-induced burnout. It’s characterised, to some extent, by your brain simply refusing to do things you were previously supposedly able to do (skilled things: like doing presentations in front of big audiences, being a people-person at work or socialising in groups, and basic things: like deciding what to cook or navigating a supermarket) - all brought about by trying, for a life-time, to keep up with the expected way of doing things and the quantity of activity that ‘most people’ seem to manage.

It was a strange thing to acclimatise to. I wasn’t exactly sad, or down. In fact, I still enjoyed existing - possibly protected from feeling depressed by some sort of inherent neurodivergent joy for simple things like cheese, seeing a new plant, or chopping wood (a sensory joy that I believe is the opposite to the sensory overload you get from wearing the wrong socks or the fridge being too loud). But for around 90% of the time, my brain simply refused. Trying to engage in cognitive function like making dinner or reading or writing a book set off a response in my brain that I’d describe as a tin can being crushed - that would trigger meltdowns.

Eventually, once I’d realised what was going on - and accepted that I couldn’t do much more than binge-watch fifteen seasons of ER without feeling like my brain was a crumpled coke can - I began to tune into the activities that made my brain feel not crumpled.

Here are some of them:

Coppicing: sawing through hazel stems after hazel stem. Following a stream to see where it goes. Taking photos of the underside of ferns. Trampling across a bog to confirm that yes, they are very tall alder trees as suspected. Making lists of medieval place-names from a map. Drawing an imaginary route across Dartmoor. Hedge-laying: solving the puzzle of which branches to cut first, which to keep. Drawing diagrams of bird-beaks. Turning my notebook sideways to write out the plot in one long line. Cutting up sticks for hours and weaving them together into a hedge like a nest. Chopping firewood. Sweeping. Digging. Map-making. Daydreaming of story-plots.

These are typical of the things that I found joy and solace in. I wasn’t seeking them out, exactly. But instinctively, I think I let myself spend more time in settings that pieced together the fried parts of my brain. Of course, I also did things that didn’t help. I spent too long scrolling; I got addicted to Tetris. I said yes to projects too soon; or took on other people’s stresses as a distraction from my own. (There’s recent research suggesting ADHD relates to how your brain burns through dopamine - so dopamine-intensive activities can be compulsive).

And now that I’m feeling a bit better, I’m able to look at what the common thread is between those activities - the times when I felt most rested and calm - the times where I most understood myself and felt most like myself. The activities that brought me back towards writing and creativity.

But what’s the theme? Is it that they’re all methodical or rhythmical processes that spark a chemical reaction in my brain? Do I get a shot of dopamine whenever I identify something correctly, or find the right route along a twisty path? Is it the joy I feel when I share my discoveries with someone? They’re all tactile, certainly. There’s something rough and natural to all of them - perhaps with a connection to the outdoors.

The best descriptor I’ve found so far is something akin to foraging. All these activities are to do with searching and finding and identifying and recording - interlaced with making or maintaining. Each of them has something to do with scanning a place - whether it’s a landscape or the page of a book - and then honing in on something of interest. My brain jumps from idea to idea in quick succession - often interrupting itself mid-thought (or out loud, mid-sentence) and jumps between fact and fiction constantly. It’s the squirrel in my brain (as Margaret Atwood notes) - bringing ideas back to its nest to tuck away. My mind is always scavenging, I think: identifying, gleaning, foraging, finding and collecting. I would not be surprised if this resonates with other authors - other naturalists - and other neurodivergent folks.

(Winter Fuel, by Millais - which captures where I’d rather be most of the time)

But in the modern world, this way of working is not really seen as an asset. In a classroom - in the workplace - on the production line - humans have to stay on track and not be distracted and pay attention. Society rewards certain kinds of productivity - keeping our attention on one project or one job or one relationship.

But before that - before Industrialisation - it surely was an advantage - in literal foraging. Being out in the landscape, attention widespread would be mean that you spotted the nuts and berries and animal tracks. Attention to details, like gills on a mushroom or the scent of a plant would ensure that there was someone in the group who could forage safely. Experimenting, fidgeting, playing - not sitting still - it was all valuable in experimentation and innovation - discovering new methods of hunting or making tools (followed by a spot of info-dumping and insisting on being right, to make sure your innovations were used properly).

I’m not a researcher - so I don’t propose this as a rigorous theory. I think it risks leading down some quite ableist roads (I’ve already seen some research praising the evolutionary value of ‘high-functioning’ neurodivergence which seems pretty dodgy). But both ADHD and Autism have long been diagnosed based on how you exhibit certain negative symptoms that have an inconvenient impact on others or don’t meet certain expectations of behaviour (like being hyper-verbal, or fixated on certain interests, or easily distracted) instead of looking for positives. I’ve worked with many students who simply hadn’t been told that their deficits could be strengths in the right context - and many more students whose strengths and passions are hidden because they have higher support needs (like being non-speaking) haven’t ever had enough support or stability to communicate or experience these.

It’s also important that we don’t go too far the other way and try to get everyone to look on the bright side of neurodivergence, because the reality of modern society means the ‘bright sides’ are only really advantages from positions of privilege. Financial stability, access to the outdoors, opportunities to advocate for your rights and accommodations are all things that reduce the struggles of neurodivergent people - and they’re limited. Neurodivergence is - like much else - also an issue of class and race. It’s especially telling that writing and nature - two activities that can provide a lot of comfort to neurodivergent folks - are more accessible (professionally and as a hobby) to neurodivergents who aren’t doubly marginalised.

Understanding my neurodivergence allows me to work to my own strengths, in writing and in life - but perhaps just as importantly, it educates me about my barriers. I struggle to filter out detail. My writing often starts out dangerously descriptive and needs thinning out. And when I’m writing, I’m constantly fighting against the noise around me - and the lights too. Often, noise cancelling headphones and caffeine aren’t enough to get me through the swamp of ideas - where I’m supposed to pull sentences out of the mud and separate them from the infinite other possibilities of where a story could go. I cannot, currently, reach the same level of productivity as other writers - especially not while supporting another person with chronic illness & disability.

It’s interesting for any writer (indeed, any person) to pause and reflect on how their brains work. For the neurodivergent writer, I think it can be really empowering on a personal level - to give us the confidence to write our stories - to take the time we need - to advocate for support - to spend time with those topics that interest us. But I also think it’s empowering on a greater level - because neurodivergence is so tied in with radical thinking - with queerness - with disability justice - with climate justice and decolonisation - with people frustrated by a society that encourages burnout and rewards conformity, and thrives on personal exhaustion that leaves us with no energy to fight for what we think is right.

* * *

Afternotes

*I meant to write more in this blog about the metaphor of foraging and writing. As I went off on one, I’ll keep that for another blog about writing.

** I know it seems like I’ve only just discovered radical thinking - apologies to my readers who are lifelong radicals

*** As you know, I love William Blake - so I’ve carefully avoided talking about Blake & Neurodivergence and Radical Thinking in every paragraph here